Spiritual Expression in the Romantic Era

In Romantic art, nature—with its uncontrollable power, unpredictability, and potential for cataclysmic extremes—offered an alternative to the ordered world of Enlightenment thought.

“… all that stuns the soul, all that imprints a feeling of terror, leads to the sublime.” – Denis Diderot

In French and British painting of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the recurrence of images of shipwrecks and other representations of man’s struggle against the awesome power of nature illustrates this view. The Raft of the Medusa became an icon of the emerging Romantic style.

The Raft Of The Medusa,1819, Theodore Gericault

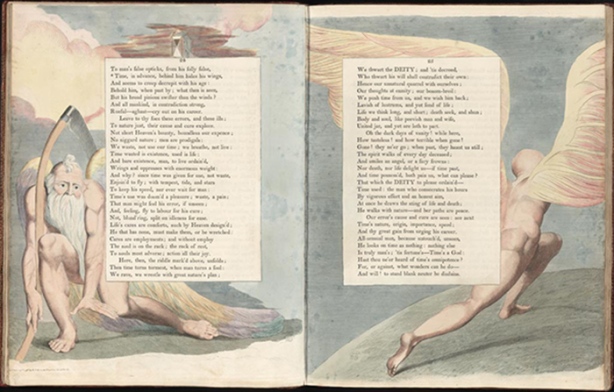

William Blake

William Blake (1757-1827) is a mystical artist and poet whose work was born out of authentic spiritual vision. Against all authority, he devised his own personal mythology to illustrate his mystical view of the universe. He was one of the most original visual artists of the Romantic era. Whereas notable contemporaries such as J. M. W. Turner and John Constable found the subjects of their art in the landscape, Blake sought his (primarily figural) subjects in journeys of the mind.

Influences

Born in London in 1757 into a working-class family with strong nonconformist religious beliefs, Blake first studied art as a boy, at the drawing academy of Henry Pars. He served a five-year apprenticeship with the commercial engraver James Basire before entering the Royal Academy Schools as an engraver at the age of twenty-two. His conventional training was supplemented by his private study of medieval and Renaissance art, Blake sought to emulate the example of artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo, and Dürer in producing timeless, “Gothic” art, infused with Christian spirituality and created with poetic genius. (Ref)

Reverent of the Bible but hostile to the Church of England – indeed, to all forms of organised religion – Blake was influenced by the ideals and ambitions of the French and American revolutions, as well as by such thinkers as Jakob Böhme and Emanuel Swedenborg.

William Blake, The Ancient of Days Setting a Compass Upon the Face of the Earth ( Proverbs, viii. 27), Frontispiece to “Europe: a Prophecy,” printed 1794

Techniques

Blake did not like oils , but devised a wholly original method of “relief etching,” which creates a single, raised printing surface for both text and image. The relief-etching of the illuminated books such as Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), along with the line-engraving or intaglio printing of the illustrations of the Book of Job (1825) and Dante (unfinished at his death), utilize different and opposite techniques: as such they can be interpreted on the one hand as representing the visionary form and spiritual unity of Blake’s imagination and on the other, the power of pure line engraving to evoke tradition and the perfect union of style and content. (Ref)

His illuminated printing involved writing the text of the poems on copper plates with pens and brushes, using an acid-resistant medium. He then etched the plates in acid to dissolve the untreated copper and leave the design standing in relief (hence the name). This is a reversal of the usual method of etching, where the lines of the design are exposed to the acid, and the plate printed by the intaglio method, designed to facilitate the mechanical reproduction of images for mass consumption. (Ref)

Pouring Acid onto a Copper Plate: Blake’s Relief Etching Method

His technique tries marry form and content, body and soul.

But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul is to be expunged; this I shall do, by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.

William Blake, Jerusalem

Blake described his technique as “fresco,” using oil and tempera paints mixed with chalks, Blake painted the design onto a flat surface (a copperplate or piece of millboard), from which he pulled the prints simply by pressing a sheet of paper against the damp paint. He finished the designs in ink and watercolor, making each, rare, impression unique, using yellow ochre, green, and raw sienna pigments mostly in the early years, which were the least expensive pigments in London at the time

Relief-etched plate on the bed of the press and impression before watercolors and pen and ink finishing.

Relief etching allowed Blake to control all aspects of a book’s production: he composed the verses, designed the illustrations, printed the plates, coloured each sheet by hand, and bound the pages together in covers. The resulting “illuminated books” were written in a range of forms—prophecies, emblems, pastoral verses, biblical satire, and children’s books—and addressed various contemporary subjects—poverty, child exploitation, racial inequality, slavery, tyranny, religious hypocrisy.

Although Blake has become most famous for his relief etching, his commercial work largely consisted of intaglio engraving, the standard process of engraving in the 18th century.

Blake’s Vision

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with Sun (1805) is one of a series of illustrations of Revelation

He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star. – William Blake

William Blake who had experienced visions since his childhood, and throughout his life can be described as a mystic, but he also had an amazing insight into contemporary economics, politics and culture, and was able to discern the effects of the authoritarianism of church and state as well as what he considered the arid philosophy of a rationalist view of the world which left little scope for the imagination. He abhorred the way in which Christians looked up to a God enthroned in heaven, a view which offered a model for a hierarchical human politics, which subordinated the majority to a superior elite. He thus challenged this depiction of God as a remote monarch and lawgiver, and the use made of such imagery to justify authoritarianism. (Ref)

“May God us keep from Single vision and Newton’s sleep.” Blake

Newton (1795-1805)

He also criticised the dominant philosophy of his day which believed that a narrow view of sense experience could help us to understand everything that there was to be known.

“Would to God that all the Lord’s people were prophets”, he wrote, thereby including everyone in the task of speaking out about what they saw. Prophecy for Blake, was not a prediction of the end of the world, but telling the truth as best a person can about what he or she sees. (Ref)

Spirit of a Flea

Swedenborg’s theory that natural phenomena actually represent, or rather shadow, unseen spiritual conditions and existence can be seen as reflected in much of Blake’s work.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up till he sees all things through narrow chinks in his cavern.” – William Blake

To Blake all things exist in the human imagination,” and “in every bosom a universe expands.” He believed that in the human imagination lay man’s only source of divine illumination. Blake used his visions as the inspiration for his art.

The Crucifixion: `Behold Thy Mother’ (1805), William Blake

His Influence

Blake’s apocalyptic and revolutionary beliefs, as expressed in his art, never found a popular audience during his lifetime and he was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views. His paintings and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and “Pre-Romantic”. Although Blake struggled to make a living from his work during his lifetime his influence and ideas are possibly the strongest of all the Romantic poets and artists on the twentieth century.

Blake’s work was neglected for a generation after his death and almost forgotten when Alexander Gilchrist began work on his biography in the 1860s. The publication of the Life of William Blake rapidly transformed Blake’s reputation, in particular as he was taken up by Pre-Raphaelites, in particular Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne.

While Blake had a significant role to play in the art and poetry of figures such as Rossetti, it was during the Modernist period that this work began to influence a wider set of writers and artists. William Butler Yeats, who edited an edition of Blake’s collected works in 1893, drew on him for poetic and philosophical ideas, while British surrealist art in particular drew on Blake’s conceptions of non-mimetic, visionary practice in the painting of artists such as Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland.

After World War II, Blake’s role in popular culture came to the fore in a variety of areas such as popular music, film, and the graphic novel.Blake had an enormous influence on the beat poets of the 1950s and the counterculture of the 1960s, frequently being cited by such seminal figures as beat poet Allen Ginsberg, songwriters Bob Dylan, Pete Doherty, Jim Morrison, Van Morrison, and English writer Aldous Huxley.

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin “Christ in the Garden of Olives” 1889

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin ( 1848 – 1903) was known for his experimental use of colors in the Synthetist style and the closely related movement Cloisonnist style which was directed at the appearance of forms. Line and colour, as well as the artist’s personal response to those forms was integral in Synthetism. Sythetism placed emphasis on the two dimensional plane that were influential to the French avant-garde and many modern artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

The Yellow Christ (Le Christ jaune), 1889

His The Yellow Christ (1889), is often cited as a quintessential cloisonnist work. Gauguin reduced the image to areas of single colors separated by heavy black outlines. In such works he paid little attention to classical perspective and boldly eliminated subtle gradations of colour.

“The yellow color links Christ to the landscape… The agricultural cycle is seen as a parallel to the religious cycle of Christian life – birth, life, death, and rebirth in Heaven. It also follows more specifically the Passion Cycle of Christ: fall, when crops are harvested, would be equivalent to the crucifixion; then follows winter, when nothing grows, parallel to Christ’s three days in the tomb; and finally springtime arrives, when everything comes back to life, a celebration like Christ’s resurrection.” (Ref)

Gauguin was also an important figure in the Symbolist movement as a painter, sculptor, print-maker, ceramist, and writer. The major themes of the Symbolist movement expressed longings for transfiguration “anywhere, out of the world” and is related to the gothic component of Romanticism. Symbolism was a reaction against naturalism and realism, anti-idealistic styles which were attempts to represent reality as it is, and to elevate the humble and the ordinary over the ideal. Symbolism was a reaction in favour of spirituality, the imagination, and dreams.This name came from the artists’ desire to create art that symbolizes thoughts, feelings, and experiences. In the late 1800s, the idea of painting to convey emotion rather than physical reality was truly revolutionary. (Ref)

Machinery Section at the Great Exhibition of 1851

The Industrial Revolution began in England in the middle of the 18th Centuary,and by the late 1800s the automobile, airplane, camera, and telephone were invented. As the industrial age, Western society witnessed a significant change – the birth of sprawling cities, urban culture, mechanized production, and an increasing emphasis on capitalism. It was in this time that the modernist movement also came about, questioning the new world order that industry and machinery were creating. Many modernists noted that modern society has also been industrialized in a sense, and that personal lives had degraded to an artificial, mechanized, and impersonal routine. (Ref)

Unlike the Impressionist artists before him, Gauguin was a member of a group of painters and poets who sought to escape the stress of the modernizing world. Many Impressionist painters created scenes of modernity and city life using large brushstrokes and textured surfaces. Gauguin too painted with large brushstrokes and patches of color but instead of depicting European modernity, Gauguin painted serene images of the pre-industrial world which paved the way to Primitivism and the return to the pastoral.

Raro te Oviri, 1891

Spirituality in Gauguin’s Work

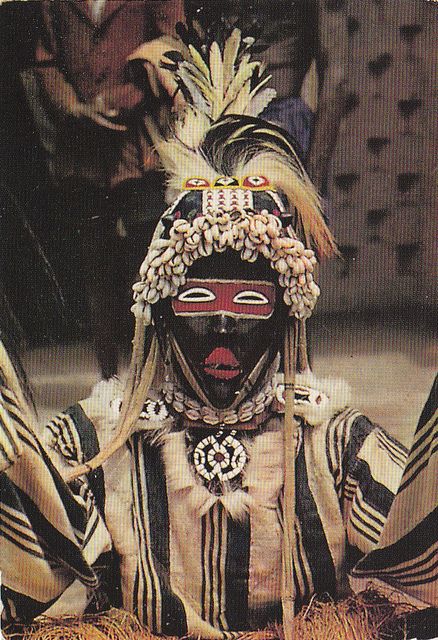

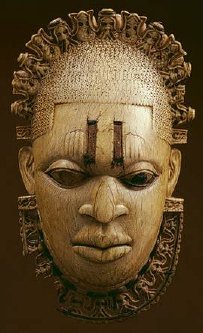

Gauguin’s interest in non-European culture was thus part of the nineteenth-century European colonialist interest of “going native” in order to distance themselves from European society and to discover a native “authenticity” through experience and cultural knowledge. It is within the cultural and political framework of the nineteenth century and the larger movement of spiritual universalism that Gauguin developed a personal interest in non-European forms of spirituality. Gauguin’s association with the Theosophists and his references to Buddhism, Hinduism, Sufi mysticism, and Tahitian religion in his paintings are products of his individual interests as well as products of colonialism. His interest in different religions and spirituality become his primary means of depicting other cultures as well as his own. (Ref)

Spirit of the Dead Watching 1892

In your light I learn how to love.

In your beauty, how to make poems.

You dance inside my chest,

where no one sees you,

but sometimes I do,

and that sight becomes this art.

Rumi

A common theme among all religions is the need for an origin story. It was this search for origin stories that became a dominant theme to his religious works as well as his self-portraits, and lead him to search out places closer to an idyllic Paradise.

In order to find appropriate subject matter Gauguin traveled to the quaint countryside of Brittany, France, and later to the island of Tahiti and the Marquesas. Gauguin wanted to return to an earlier period of civilization in which mystical rituals and ancestral worship provide a mythical, rather than rational, system of meaning.

It is suggested that Paul Gauguin’s interest in origins is synonymous with his desire to cast himself in the roles of different religious figures in his paintings, and that his self-portraits and religious works are a means of working out his questions and uncertainty regarding his personal beliefs and spiritual existence. His taking on of other roles and his shifting modes of self representation in self-portraits, writings, and other works provide viewers and readers with a fluid understanding of a man seeking answers to the great questions of existence.

He for example paints Self-Portrait with Halo, which recalls the Christian creation narrative in Genesis through the symbols of the snake and apples, and casts himself in the dominant role. As Gauguin had a lifelong interest in questions of identity, it is reasonable to interpret his symbolic role-play as a form of identity exploration. Gauguin, however, never places himself within his Tahitian scenes of landscape, daily life, or religious ceremonies. His choices to include himself in his Christian works and to remove himself from his Tahitian paintings shows his role as ethnographic observer; a witness rather than a participant. Although Gauguin removes himself from Europe and the European settlement in Tahiti, he calls attention to his identity as a European within a foreign colony on account of his status, appearance, and relationship with the native population. (Ref)

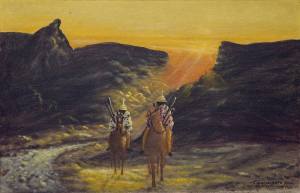

White Horse, 1891

Gauguin painted the White Horse during his second stay in Tahiti. He liked to roam through the countryside and explore the mountains and forests of the interior. These out-of-the-way places swarmed with all sorts of wildlife and plants which enchanted him. (Ref)

Analysis from Musée d’Orsay

This scene was however, not taken from real life; it is an imaginary, synthetic vision of a Tahitian landscape. The contorted branches of a native tree called bourao, a sort of hibiscus, along with lilies and imaginary flowers in the foreground make a decorative frame for the main motif. The sky and the horizon are locked out of this enclosed space.

A white horse, its coat tinged with the green of the vegetation, has given the painting its title. It is drinking, standing in the middle of a stream which flows vertically through the composition. The solitary animal probably has a symbolic meaning related to the Tahitians’ beliefs about the passage of the soul into another world. In Polynesia, white is associated with death and worship of the gods.

Behind the sacred animal, two nude figures are riding bareback into the distance. The tiered arrangement of these three animated motifs in the landscape accentuates the vertical, flat vision of the scene. To intensify the decorative effect, Gauguin has used a sumptuous palette. The greens – from grass green to emerald – and the deep blues contrast with orange and pink notes and the coppery colour of the riders’ skin.

An impression of paradisiacal serenity emanates from this canvas which has become a veritable icon. The pharmacist in Tahiti who commissioned the picture did not appreciate Gauguin’s daring use of colour. He refused it on the grounds that the horse was too green.

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? 1897

Gauguin had received a seminary education in his youth. His religious beliefs never deserted him although he increasingly questioned the strictures of the traditional Catholic church. This questioning reached a peak during his last years in Tahiti – when he was dying, destitute, isolated from the Tahitians because of his illness, and mourning the death of one of his daughters.

Gauguin vowed that he would commit suicide following this painting’s completion. After completing this masterpiece Gauguin failed in his attempt to kill himself and continued to paint for another six years.

The painting is meant to be read as a story – from right to left, with the three major figure groups illustrating the questions posed in the title. Initially, an age of childhood is shown, followed by youthfulness and the daily activities of adulthood. Lastly, on the left-most side, the aged and contemplative is shown as a final stage in life. The painting is also rich with symbolism, which serves to convey more spiritually related messages.

In this work Gauguin asks broad, philosophical questions about identity, meaning, and the afterlife. Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? This painting can also be seen as a composite work that incorporates figure studies, religious imagery, and animals all within a Tahitian landscape. The title of the work and Gauguin’s own religious and cultural position support the interpretation that the painting is the culmination of his personal research into with unfamiliar cultures and religious beliefs.

The central figure reaching above his head for an apple from the Tree of Life and recalls Adam or Eve in a pastoral setting, suggesting that the painting it is a type of Tahitian Genesis scene. The Christian idea that all human folly originates from this singular moment explains why Gauguin placed the figure in the center of the canvas. The figure and the scene from Genesis directly answer Gauguin’s first question for followers of the Christian faith. (Ref)

Similarly, Gauguin incorporates figure groups from his other canvases to form a pastiche. The nude figures in the lower right of the painting can also be seen to form a nativity scene complete with animals, and this group continues the theme of society’s origins. Jesus becomes a second Adam whose birth leads to the redemption of humankind and represents his own beginning on earth. Gauguin also includes an homage to artistic origins, citing Degas’ bathers by including the two crouching nude figures whose backs are turned toward the viewer. Although Gauguin incorporates fragments of other works of his own and others, the painting itself is a complete work with the unifying theme of a search for meaning. It also refers to the Gnostic belief in second baptism.

He attempts to reconcile the uncertainty of human origin and the fate of the soul in a way that traditionally derives from one’s religious beliefs. Gauguin’s curiosity about being and his engagement with other cultures led him to explore meaning through the archetypal symbols of religion. Although Gauguin believed that Christ’s model was an ideal one for humans to emulate, he did not believe that Christ was the only such model. He believed, for example, that Buddha was another ideal example of what humanity could become.

Visually, Gauguin includes figures from the story of Christian origin, the Hindu pantheon, and Tahitian religion. It is possible that the idol in the background is possibly not a Tahitian religious artifact, but another icon (probably Buddha-inspired) as by the time Gauguin arrived in Tahiti, “virtually nothing remained of the ancient Tahitian religion and mythology…” and the predominant religion was Christianity through missionary work. Gauguin however, was familiar with Tahitian cosmology and refers to particular deities in his writings and art, so that Scholars generally assume that the figure is the goddess Hina whose mystical union with Ta’aroa results in the birth of the universe.

This indicates that Gauguin had ignored the fact that Christianity was the dominant religion, and sought to represent the spiritual beliefs of the ‘primitive’ people through an idol that is less familiar to Western society. In a way, he is trying to allude towards the original, untouched spiritual culture and religion of the Tahitians before the process of colonization began. (Ref)

Gauguin also uses unconventional images and style as a means of rebelling the dogma he decried in his letters and notebooks. The backdrop of the painting, especially in the right half, seems to be clearly out of proportion with flattened areas and a lack of three-dimensional space. This is in fact a method Gauguin employs to abstract away from nature and express his primitivism.

He uses lack of natural scale to convey the state of the mind, rather than a physical observation – he is abstracting away from nature to express his feelings and emotions. This can be viewed as the early age of abstract expressionism and the Symbolist movement in which the goal is emotional expression and the odd proportions are a tool for achieving it

By contrasting and balancing western illusionism with non-western patterning, uniting Christian and non-Christian religious symbols, using religious morality tales as vehicles for narratives about eroticism and the abundance of nature. Gauguin breaks open myths which are well-known, uses their structure but fills them with contradictory and new meanings. Through his radical treatment of color, shape, and myth, he becomes a model for the 20th-century abstraction of Kandinsky and the later 20th-century surrealist goals of revitalizing mythology. (Ref)

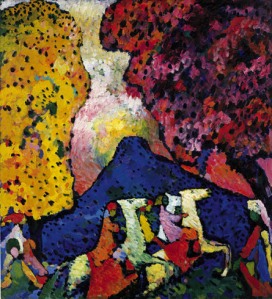

Wassily Kandinsky, “Rider of the Apocalypse”. 1911

Expressionism

Expressionism developed during a period of history that saw Germany undergo severe social, political, and economic dislocation following the country’s defeat in World War I. There was a widespread feeling of anxiety, a feeling of loss of authenticity and spirituality. German Expressionism conveyed a feeling of chaos through dark violent images that reflected the state of mind of both the artist and society in general.

They depicted the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas. Expressionist artists sought to express meaning or emotional experience rather than physical reality. Abstraction’ stood for metaphysical anxiety, and primordial psychic anguish associated with jarring formations and non representational, abstract art. (Ref)

Crucifixion, Nolde, Emil [German, 1912

From 1911 European avant-garde art was divided between two needs: the need for individual subjective expressiveness and a striving for order in a time of pending chaos. Both needs were rooted in a desire to escape through an inward journey into feelings or to an ideal structure. Both needs were part of the culture shock that swept Europe at the beginning of the century, as the implications of the Industrialization were sinking in. The avant-garde artists tried to create a new language to respond to these needs: the Cubists searched for a near scientific logic to the construction of the world and the Expressionists sought the answer in the irrational and a return to a more primal spiritual state. (Ref)

For the Expressionists, art and religion were closely intertwined, as both involved surrender to an inner, spiritual energy and a preoccupation with the human soul. Although they lived in an age of intellectual skepticism and philosophical nihilism, the Expressionists were still drawn repeatedly to the Christian themes and motifs that had shaped German life and culture for centuries.

A desire to comprehend events in spiritual terms was reflected in the artists’ recurrent images of prophets and seers, and the belief that theirs was an age of apocalyptic transformation manifested itself in various archetypally Christian motifs of creation and rebirth. The incomprehensible horror of World War I led several artists to turn to Biblical themes of salvation and redemption, and to the woodcut technique, which had a strong association with German medieval and Renaissance religious imagery. (Ref)

There were two schools of German Expressionism. Whereas Die Brücke (The Bridge) focused on the depicting the spiritual inner struggle, Der Blaue Reiter, (The Blue Rider) spiritual depictions were of a more mystical nature.

Where the Brücke artists used distortion to signal tensions in the artist and sharpen viewers’ responses, Blaue Reiter artists typically wished to involve us in a more meditative communication. Whereas some of the Brücke artists wished to be seen as 20th-century Germans developing a truly German art in a country too long dominated by French values and manner, the Blaue Reiter circle was of its nature international, and viewed art in global, even eternal terms. Der Blaue Reiter was defined by its focus on the spiritual and also on a more personal experience of art. For these artists, synthesis meant the unity of stylistic development in terms of color, which was linked to mysticism. (Ref)

Der Blaue Reiter combined two currents: the general European Expressionism and French Fauvism and added to these currents an interest in inner and mystical construction, stemming from Theosophy. Despite the close affinity between Der Blaue Reiter and the Fauves, the approach to art making was radically different—the French artists were more interested in a formal extension of Post-Impressionism while the German artists were interested in mysticism. (Ref)

Max Beckmann, Descent from the Cross, 1917

In this work, painted in the midst of a seemingly never-ending war, Max Beckmann focuses on corporeal suffering. His controlled application of color conveys the lifelessness of Jesus’s body, which is covered in bruises and still mirrors the shape of the cross in its rigor mortis. Black blood pools around the gaping holes of the stigmata. Beckmann was influenced by the exaggerated depictions of bodily decay and torment he saw in medieval German paintings. (Ref)

Emil Nolde, Christ and the Children, 1910

Emil Nolde’s heavily textured brushwork conveys the intensity of religious belief. He contrasts the innocent faith of the children, who all appear in rich, warm tones, with the restrained and cool blues of the skeptics to Christ’s left. (Ref)

Otto Dix, The Nun, 1914

Otto Dix portrays a nun’s internal struggle between her hope for eventual heavenly rewards and her desire for immediate worldly pleasures. The jarring, acidic colors on the nun’s face and hands contrast sharply with the anguish and torment conveyed by her downcast eyes and furrowed brow. The deep lines and fractured planes of her face parallel the soaring vaults of the Gothic cathedral. (Ref)

Der Blaue Reiter, led by Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky, wanted to create the blueprints for an enlightened and liberated society which emphasized spirituality as opposed to cold industrialization.

Marc and Kandinsky shared similar ideas on art: both believed that true art should possess a spiritual dimension. For Marc the spiritual aspect of art was more concerned with representing the inner soul of a being, and Kandinsky represented the spiritual by abstract means.

In Blue Horses also called The Large Blue Horses the simplified and rounded outlines of the horses are echoed in the rhythms of the landscape background, uniting both animals and setting into a energetic and harmonious organic whole. Like the Byzantine religious icons which Marc was familiar with, which were meant as an aid for the worshipper in prayer, and an encouragement to contemplate the life of the saint or the biblical figure depicted, Marc invites the viewer to connect with the animals in his paintings and to contemplate the spiritual beauty that he strove to depict.

His paintings are, more often than not, devoid of humans as though it is an animal-only world. When viewing it, humans are allowed to become a part of the work it, since the viewpoint is often at the level of the animal. The viewer is given the chance to get closer to the animals in his paintings and experience their beauty. Marc’s compositions, especially those before the influence of Orphism and Futurism, are often formed by a sculptural mass of animals at the centre of the picture plane, with curved lines dominating in order to underline the sense of harmony, peace, and balance.

Die Grossen Blauen Pferde (The Large Blue Horses) demonstrates this compositional technique, and together all of these elements further emphasise the spiritual beauty of the animals depicted.

I am trying to intensify my feeling for the organic rhythm of all things, to achieve pantheistic empathy with the throbbing and flowing of nature’s bloodstream in trees, in animals, in the air. Franz Marc

Marc was a deeply religious person and his depiction of animals and nature reflects this “pantheistic empathy,” which is the belief that beauty is equated with God, and that God is present in nature and all substance. Marc uses animals as his chosen means of expression just as the human figure was for Michelangelo. Marc was primarily concerned with representing the spirit and thus the beauty of the animals, in order to represent a sense of the pantheistic.

Blue is the male principle, astringent and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, gay and spiritual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy and always the colour to be opposed and overcome by the other two.

Franz Marc painted animals in symbolic colors, especially the primary colors: red, yellow and blue. Marc devised an elaborate theory of art and its colors—blue was masculine and spiritual and yellow was female and joyful—and used them to indicate the inner life of the animals, not the animals themselves.

Franz Marc, The Tiger

He did however on occasion deviate from strictly sticking to this in for example The Tiger which is depicted in yellow but the sense of playfulness and joy, as outlined in Marc’s colour theory, is far from the mood evoked. In this painting it is the geometrical composition and angular shapes and lines which dominate as opposed to colour. Marc has used shapes and lines here in order to convey the sense of terror. This was perhaps necessary when his colour theory did not allow for sinister moods or emotions to be represented. (Ref)

Franz Marc, 1913, The Tower of Blue Horses

In contrast, the Turm der Blauen Pferde (Tower of Blue Horses) (1913; missing since the Second World War and known today through reproductions considered to be one of his masterpieces), is exemplary of Marc’s dogmatic application of his colour theory. The Tower of Blue Horses draws strength in its unification of colour and composition. His belief in blue as the “male principle, stern, and spiritual” is here underlined through the verticality of the composition, which emphasises male virility and strength, yet still maintains a sense of elegance and spirituality.

Franz Marc, The Trees Show their Rings, the Animals their Veins, 1913

Around 1912 and the years leading up to the First World War, his work and representations of animals began changing. The animals within these compositions become smaller and are often spread out; the sense of calm and contemplation is absent since the picture plane begins to be cut up and divided by lines and geometric forms through the influence of Cubism, Futurism, and Orphism. There are more evidence of human life, as in The Unfortunate Land of Tyrol as Marc’s idealised animal kingdom begins to give way to reality. Animal Destinies, The Trees Show their Rings, the Animals their Veins, 1913 typifies this period. (Ref)

This work is also characteristic of the sense of apocalypse and doom which began to taint Marc’s work at this time and could be related to his feelings on the impending war. In a 1915 letter to his wife Maria, Marc explains that this change in his art occurred because he began to see the ugliness in animals which he had previously thought only existed in humans. He states that he was no longer able to see the beauty which animals had once represented for him.

The animal motifs which once conveyed a sense of emotion no longer held their appeal and possibility. The application of paint and the division of the

picture plane through the use of lines and geometric shapes now carried the emotional charge previously conveyed by animals. This change may be related to Marc’s ideas on the impending war. Marc no longer saw animals as separate entities in their own perfect kingdom, as he had once represented them. At the point when Marc began to identify the ugliness in animals, he recognised them as part of the universe which man also inhabited and which was in need of redemption. (Ref)

In Marc’s very final works before the outbreak of the First World War, it is extremely difficult to identify any animals, since non-representational form and abstraction have taken over. Fighting Forms is dominated by two swirling shapes, one red and the other black. Some claims that the red form on the left is an abstracted the image of an eagle with beak-like and claw-like shapes. If this had been Marc’s intention, it would seem, therefore, that even when his art appears to be the furthest from his earlier representations, the use of animals as emblems of emotions and expression is still prevalent. The image of war is thus perhaps represented here by a bird of prey and the conflict in the contrasting colour shapes.(Ref)

Fighting Forms may be viewed as a composition on violence and, have lost the “prettiness and polish” of his earlier works. His identification of the harsh realities of the world, led him to depict what he believed to be purer and more beautiful than man, namely animals. Since at the end of his career Marc could no longer recognise the beauty and purity in animals, as he had once been able to, and with his country on the threshold of war, it seems that he could no longer create an idealised world but had to bow to reality.In 1914, with the outbreak of the First World War (1914-18) Marc volunteered for military service, and in 1916 was killed in action, at the age of 36. (Ref)

Like Marc, Wassily Kandinsky believed that colors had symbolic meanings, but his theories stemmed from his readings of Theosophy, especially those of Rudolf Steiner, a follower of Madame Blavatsky. Involved in the realm of the spiritual, Kandinsky ceased to even see reality itself and he replaced the objects that once populated his paintings with his “inner aspiration,” which led to his development of pure abstraction. (Ref)

Theosophy influenced many late-19th- and early-20th-century artists. The Theosophical Society, was founded 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. Kandinsky’s belief in the spiritual power of art, and that the artist was a kind of messiah or prophet (or even magician) whose job it was to communicate a higher truth to humanity, stem from Theosophy. The Theosophy philosophical or religious teaching encouraged mystical insight into the nature of God and the world through direct knowledge, philosophical speculation, or a physical process, such as painting. Deeper spiritual – , or transcendental states were achieved through intuition, meditation, and other practices, common to many mystical belief systems.

‘Our minds are infected with the despair of unbelief, of lack of purpose and ideal. The nightmare of materialism which has turned the life of the universe into an evil, useless game, is not yet past; it holds the awakening soul still in its grip.‘ Kandinsky

To Kandinsky colours on the painter’s palette evoke a double effect: a purely physical effect on the eye and a deeper effect, causing a vibration of the soul or an “inner resonance”—a spiritual effect in which the colour touches the soul itself.

For example; yellow is a typically terrestrial colour, whose violence can be painful and aggressive. Blue is a celestial colour, evoking a deep calm. The combination of blue and yellow yields total immobility and calm, which is green. For him clarity is a tendency towards white, and obscurity is a tendency towards black. White is a deep, absolute silence, full of possibility. Black is nothingness without possibility, an eternal silence without hope, and corresponds with death. The mixing of white with black leads to gray, which possesses no active force and whose tonality is near that of green. Gray corresponds to immobility without hope; it tends to despair when it becomes dark, regaining little hope when it lightens.

In his writings, Kandinsky also analyzed the geometrical elements which make up every painting—the point and the line. He called the physical support and the material surface on which the artist draws or paints the basic plane, or BP. He did not analyze them objectively, but from the point of view of their inner effect on the observer.

A point is a small bit of colour put by the artist on the canvas. It is neither a geometric point nor a mathematical abstraction; it is extension, form and colour. This form can be a square, a triangle, a circle, a star or something more complex. The point is the most concise form but, according to its placement on the basic plane, it will take a different tonality. It can be isolated or resonate with other points or lines.

For example; a horizontal line corresponds with the ground on which man rests and moves; it possesses a dark and cold affective tonality similar to black or blue. A vertical line corresponds with height, and offers no support; it possesses a luminous, warm tonality close to white and yellow. A diagonal possesses a more-or-less warm (or cold) tonality, according to its inclination toward the horizontal or the vertical.

Wassily Kandinsky’s use of the horse-and-rider motif symbolized his crusade against conventional aesthetic values and his dream of a better, more spiritual future through the transformative powers of art.

In 1909, the year he completed Blue Mountain, Kandinsky painted no less than seven other canvases with images of riders. In that year his style became increasingly abstract and expressionistic and his thematic concerns shifted from the portrayal of natural events to apocalyptic narratives. By 1910 many of his abstract canvases shared a common literary source, the Revelation of Saint John the Divine; the rider came to signify the Horsemen of the Apocalypse, who will bring epic destruction after which the world will be redeemed.

The Apocalypse is a common theme among Kandinsky’s first seven Compositions. Writing of the “artist as prophet” in his book, Concerning the Spiritual In Art, Kandinsky created paintings in the years immediately preceding World War I showing a coming cataclysm which would alter individual and social reality. Raised an Orthodox Christian, Kandinsky drew upon the Jewish and Christian stories of Noah’s Ark, Jonah and the whale, Christ’s resurrection, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse in the book of Revelation, Russian folktales and the common mythological experiences of death and rebirth. Never attempting to picture any one of these stories as a narrative, he used their veiled imagery as symbols of the archetypes of death–rebirth and destruction–creation he felt were imminent in the pre-World War I world. (Ref)

In both Sketch for Composition II and Improvisation 28 (second version), Kandinsky depicted, through highly schematized means, cataclysmic events on one side of the canvas and the paradise of spiritual salvation on the other. In Improvisation 28, for instance, images of a boat and waves (signaling the global deluge), a serpent, and, perhaps, cannons emerge on the left, while an embracing couple, shining sun, and celebratory candles appear on the right. (Ref)

Wassily Kandinsky, Great Resurrection (Grosse Auferstehung) (plate, folio 52) from Klänge (Sounds), 1913

In Great Resurrection, Kandinsky combined Bavarian and Russian folk imagery with an abstracted visual language to create this frenzied scene of the Last Judgment. In the upper left, an angel trumpets the coming apocalypse. In the lower right, a kneeling decapitated figure, holding its head aloft, returns to life as foretold in the Book of Revelation. (Ref)

Composition IV and later paintings are primarily concerned with evoking a spiritual resonance in viewer and artist. he had intended the work to evoke a flood, baptism, destruction, and rebirth simultaneously. As in his painting of the apocalypse by water (Composition VI), Kandinsky puts the viewer in the situation of experiencing these epic myths by translating them into contemporary terms (with a sense of desperation, flurry, urgency, and confusion). This spiritual communion of viewer-painting-artist/prophet may be described within the limits of words and images. (Ref)

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII, 1913

Composition VII is the pinnacle of Kandinsky’s pre-World War One artistic achievement. The creation of this work involved over thirty preparatory drawings, watercolors and oil studies, documenting the deliberate creative process used by Kandinsky in his compositions. Through all of the preparatory works and in the final painting itself, the central motif (an oval form intersected by an irregular rectangle) is maintained. This oval seems almost the eye of a compositional hurricane, surrounded by swirling masses of color and form. In Composition VII’s final form, Kandinsky has obliterated almost all pictorial representation. Art scholars, through Kandinsky’s writings and study of the less abstract preparatory works, have determined that Composition VII combines the themes of The Resurrection, The Last Judgment, The Deluge and The Garden of Love. (Ref)

Tapestry, Christ in Glory, designed by Graham Sutherland, 1950s – 19662

After the Second World War spirituality and religion became disconnected. A new discourse developed, in which (humanistic) psychology, mystical and esoteric traditions and eastern religions are being blended, to reach the true self by self-disclosure, free expression and meditation.

The distinction between the spiritual and the religious became more common in the popular mind during the late 20th century with the rise of secularism and the advent of the New Age movement.

Francis Bacon’s (1909 – 1992) provocative and disturbing images carry a raw sense of anxiety and alienation. They reflect that existential fear, loathing and incomprehension at the atrocities of the Holocaust that came to light at the end of World War Two. Bacon’s art was seen as a metaphor for the corruption of the human spirit in the post World War Two era.

‘Painting is the pattern of one’s own nervous system being projected on canvas’. Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944

In 1944, one of the most devastating years of World War II, Francis Bacon painted Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. In this triptych depicting anthropomorphic creatures writhing in anguish, Bacon established his reputation as one of England’s foremost figurative painters and a ruthless chronicler of the human condition. During the ensuing years, certain disturbing subjects recurred in Bacon’s oeuvre: disembodied, almost faceless portraits; mangled bodies resembling animal carcasses; images of screaming figures; and idiosyncratic versions of the Crucifixion. (Ref)

The three ‘figures’, bestial mutations of the human form, were Bacon’s interpretation of the Furies: the three goddesses of vengeance (Alecto, Megaera and Tisiphone) from Greek mythology. Their task was to punish crimes that were beyond human justice. Bacon painted the work at the end of World War Two, as the accounts of the Nazi death camps were beginning to emerge. The three deformed ‘Figures’ were a metaphor for the corruption of the human spirit and the artist’s revulsion at man’s inhumanity to man. (Ref)

Picasso “Bathers with a Toy Boat”. 1937

The form of the Furies is borrowed directly from Picasso’s late 1920s and mid-1930s pictures of biomorphs on beaches, in particular from the Spanish artist’s The Bathers (1937).

The theme reflects human suffering on a universal scale while also addressing individual pain. The Crucifixion appeared in Bacon’s work as early as 1933. Even though he was an avowedly irreligious man, Bacon viewed the Crucifixion as a “magnificent armature” from which to suspend “all types of feeling and sensation.”The crucifixion in Bacon’s work is a “generic name for an environment in which bodily harm is done to one or more persons and one or more other persons gather to watch.” (Ref)

For Bacon there was a connection between the brutality of slaughterhouses and the Crucifixion. Bacon believed that animals in slaughterhouses suspect their ultimate fate. Seeing a parallel current in the human experience, as symbolized by the Crucifixion in that it represents the inevitability of death; “we are meat, we are potential carcasses.” (Ref)

The triptych, was a devotional format that was first used in Christian altarpieces. Bacon used this form of display for two reasons. First, exhibiting such despairingly secular subjects in a religious format could only be viewed, in the context of the time, as a calculated act of desecration that would amplify the shock value and emotive response to his images. Secondly, the adjacent frames of a triptych arrangement allow Bacon to conduct a kind of abstract or psychological narrative between the consecutive images. The idea to use a triptych format was probably inspired by the expressionist paintings of Max Beckmann which Bacon would have seen in Berlin.

Francis Bacon, ‘Study after Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X’, 1953(oil on canvas)

If Velazquez’s ‘Portrait of Pope Innocent X’ portrays the public face of power while hinting at the private flaws of the man behind it, then Bacon’s ‘Study after Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X’ broadcasts his inner psychoses.

Bacon’s Pope inhabits an ethereal world of perpetual torment – a living hell from which there is no escape. He is paralysed with pain and fear, and jolted with shocks from his golden throne which has been transformed from a symbol of authority into an instrument of torture. The composition reaches its focal point as a primal scream shrieks from the pope’s mouth. This scream echoes back to birth expressionist art – ‘The Scream’ of Edvard Munch. (Ref)

Francis Bacon’s art is full of paradox – he both repulses and seduces his audience simultaneously. He repulses them with his shocking subject matter, however, he also seduces them by the rich sensual qualities of his beautiful paint surface with its rich brushwork and expressive colour.

The same kind of contradiction confounds his subject matter. While ‘Study after Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X’ attacks the authority of the Catholic Church, the social and religious establishment of his Irish childhood, it is also part of an obsessive fascination with its iconography. Bacon, himself, revelled in such ambiguities, ‘The job of the artist is always to deepen the mystery………If you can talk about it, why paint it?’ (Ref)

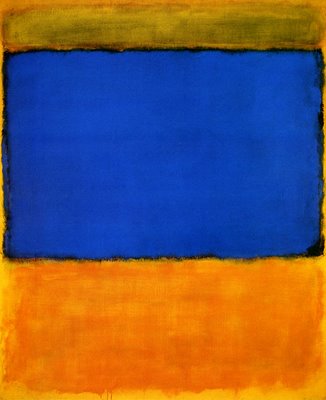

The Rothko Room at The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo © Robert Lautman

Abstract Expressionism can be divided into two kinds of paintings; Action Painting like Jackson’s Pollock’s paintings, and those that can be called still paintings, or are called Colour Field Painting, like the work of Mark Rothco.

Mark Rothko

Mark Rothko has been called a spiritual and a religious painter, but he is a religious painter for a secular age, providing what the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard called “a space to daydream”. It is a space in which we can contemplate not only the natural grandeur of the world, but the silence and stillness at the core of who we are. (Ref)

“Seeking to represent a spiritual experience, Mark Rothko invoked the power of color in his work.”

Rothko’s rectangles developed after a long maturation process, in which his painting moved from an expressionist-grounded realism, through a surrealism in which classical, mythological, and Christian subjects provided the ground for exploring the unconscious, to the final form he arrived at with his breakthrough work in 1949 that culminated in the dark murals for the Houston chapel, painted between 1964 and 1967—“imageless art that sought great religious and moral depth.” (Ref)

While Rothko was concerned about the moral and religious content of his work from the beginning, his classic period arrived a moment in the history of art and religion in American culture when both were in crisis. Post-war America, in its burst of affluence, was going through what many saw as a secularization process, while art was experiencing a crisis of representation following the exhaustion of Social Realism (William Gropper) and American Scene painting (Thomas Hart Benton).

Rothko’s response was to try to figure his sense of the discomforting of transcendence without figuration, in the pure abstraction of luminous rectangles and their sensuous suggestion of portals, their hint that something existed, perhaps a kind of light, behind the surface. By emptying the canvas of obvious story Rothko could paint a more emotionally accurate “portrait of the soul,” as he sometimes called his paintings.(Ref)

Mark Rothco,

His paintings may appear calm, even serene, inviting restful contemplation, but they are far more demanding. They require sustained attention, and what at first appears to be stillness is actually very alive, almost pulsating in the soft, undefined borders between the colors and the edges of the paintings. The blocks of color invite you into an intimacy that draws you out of yourself, but at the same time the size of the painting requires you to keep your distance. There is the sense of a presence—beyond, behind, within—but it is invisible, inexpressible.

While the paintings are completely emptied of narrative content, Rothko insisted they were not formally abstract.

“I’m not an abstractionist, I’m not interested in relationships of colors or forms or anything else.…I’m interested in only expressing basic human emotions, tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on—and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions. The people who weep before my pictures, are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.”

For some viewers, the shimmering rectangles and ambiguous relations between foreground and background, as well as the tensions among the blocks of color, suggest a mystical dialogue between absence and presence. (Ref)

Mark Rothco, No. 14, 1960

The only only valuable subject matter in paintings are the tragic and the timeless. Mark Rothco

In some ways his work serves the same purpose for the mid 20th centuary man as did the Byzantine religious icons for their contemporaries; for spiritual contemplation and focus. His work also evokes the same mood and feeling for his mid 20th centuary contemporaries as the landscapes of German Romantics did in the 19th centuary for their contemporaries. The German Romantics’ work conveyed the sublime through their landscapes where the vastness of nature overpowers man in its smallness; it is at the same time beautiful and terrifying, and it creates a feeling of longing and absence.

The Monk by the Sea (German: by the German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich. It was painted between 1808 and 1810

For Rothco nature, or a beautiful landscape could no longer express the same spiritual feelings in us as it did in the 19th centuary. It could no longer reach us with its religious language. With scientific advancement of the 20th centuary much of nature has become demystified. Powerful beings no longer speak to the modern contemporaries through volcanoes and cascades. For Rothco representational landscape no longer evoked such powerful experiences in us and reflected the spiritual crisis of the times.

He uses a vertical format that is normally used for portrait paintings, whereas horizontal format is used for landscapes, The vertical format is however, divided into horizontal bands, or blocks that can be seen as remnants of the landscape, as for him the non-representational is the only way to evoke the same powerful spiritual feeling in his contemporaries.

His works therefore reflects the sense of the sublime and attempts to speak the unspeakable, to bring the viewer into contact with that which escapes your grasp, that which is beyond things and escapes understanding, creating a strong feeling of yearning reminiscent of the feeling created in the German Romantic landscape. It leaves the viewer with a longing for that which cannot be see, cannot be grasped or understood.

Rothco Chapel, Texas

His paintings (1964 – 1967) for the Rothco Chapel in Texas, appears black at first glance, but with contemplation hues of colour emerges from black. These are said to represent “the unbearable silence of God.” The blackness and figurelessness representing a visual silence.

In a Rothco painting you have three or four different layers of thinly washed paint, hazy blocks of colour on top of colour, all interacting with each other, almost swimming into each other. It is actually not easy to establish what colours are in which layer, which adds to mystical mysteriousness of Rothco’s paintings.

We favour the simple expression of concrete thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for the flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth. Rothco and Motherwell

When you look at a Rothco painting you realize what is meant by the overall, which is often used in regard with the Abstract Expressionist’s paintings. The edges, or sides are of no less importance than the core. You cannot complete your experience of the painting without letting your eye wander all over the surface of the work. It is like being in a zone of no gravity, or a weightless zone.

Like other Abstract Expressionists he did not want his paintings to be framed. A framed painting is understood as an illusion of an imagined space or scene. For the Abstract Expressionists their work were not alluding to another space; what they were making was the reality that they wanted to present to the viewer. A frame would separate the painting’s reality from the viewer’s reality. What they wanted was a joint reality.

Like the other Abstract Expressionists’ all the traditional conventions of painting is subverted. There is none of the past illusions of representation; no focal point, no depth, no positive or negative space.

The sense of boundlessness in Rothko’s paintings has been related to the aesthetics of the sublime, an implicit or explicit concern of a number of his fellow painters in the New York School.

No. 5/No. 22, 1949

The rectangles within this painting do not extend to the edges of the canvas and appear to hover just over its surface. Heightening this sensation is the effect of chromatic afterimage. Staring at each colored segment individually affects the perception of those adjacent to it. The red–orange center of the painting tints the yellow above it with just a bit of green. The yellow above seems to tint the orange with blue. Despite these color relationships, Rothko did not want his pictures appreciated solely for their spectral qualities. He said, “If you are only moved by color relationships, then you miss the point. I’m interested in expressing the big emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom.”

No. 3/No. 13, 1949

Magenta, Black, Green on Orange follows a compositional structure that Rothko explored for twenty–three years beginning in 1947. Narrowly separated, rectangular blocks of color hover in a column against a colored ground, their edges are soft and irregular. The green bar in Magenta, Black, Green on Orange, appears to vibrate against the orange around it, creating an optical flicker. In fact the canvas is full of gentle movement, as blocks emerge and recede, and surfaces breathe. Just as edges tend to fade and blur, colors are never completely flat, and the faint unevenness in their intensity, besides hinting at the artist’s process in layering wash on wash, mobilizes an ambiguity, a shifting between solidity and impalpable depth. (Ref)

These two lectures by Jon Anderson on the The (Spiritual) Crisis of Abstract Expressionism gives an excellent perspective on the subject focusing on Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko

References

David E. Anderson, Anecdotes of the Spirit

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/episodes/by-topic/art/anecdotes-of-the-spirit/6500/

Arty Factory – Francis Bacon

http://www.artyfactory.com/art_appreciation/portraits/francis_bacon.htm

Magdalena Dabrowski, Kandinsky: Compositions

http://www.glyphs.com/art/kandinsky/

Der Blaue Reiter Painting

http://www.arthistoryunstuffed.com/der-blaue-reiter-painting-2/

Expressionism

http://www.artyfactory.com/art_appreciation/art_movements/expressionism.htm

Gauguin: Primitivism and “Synthetic” Symbolism

http://www.radford.edu/rbarris/art428/gauguin.html

Gauguin: Primitivism and “Synthetic” Symbolism

http://www.radford.edu/rbarris/art428/gauguin.html

Guggenheim – Francis Bacon

http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/artwork/293

Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art

http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=3275590

Bronner Kellner – Expressionism

http://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/Bronner_Kellner.pdf

Gabi La Cava, The Expressionist Animal Painter Franz Marc

http://www.csa.com/discoveryguides/marc/overview.php

Irene Lanridge, William Blake – A Study of His Life and Art Work

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/37407/37407-h/37407-h.htm

Daanish Maqbool, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

http://www.researchusa.org/uploads/avi/0yotxHg10USpFLcPhsQJ.pdf

Metropolitan Museum of Art – William Blake

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/blke/hd_blke.htm

MoMa Learning, Abstract Expressionism

http://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/abstract-expressionism/the-sublime-and-the-spiritual

MoMa – Expressionism

http://www.moma.org/collection/details.php?section_id=T027175&theme_id=10959

http://www.moma.org/explore/collection/ge/themes/religion

Musée d’Orsay – Gauguin, White Horse

http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/

New York Times article on William Blakefrom 1910

Nancy Spector, The Blue Mountain

http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/artwork/1844

Swindle, Stephanie Nichole, Paul Gauguin and Spirituality

https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/paper/10734/

Sue Hubbard, Rothko Retrospective

http://www.newstatesman.com/art/2008/10/rothko-paintings-late-tate

The Art Story – Expressionism

http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/ARTH208-3.4.1-Expressionism.pdf

The Art Story – Paul Gauguin

http://www.theartstory.org/artist-gauguin-paul.htm

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon_(artist)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Blake

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expressionism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Gauguin

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Studies_for_Figures_at_the_Base_of_a_Crucifixion

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wassily_Kandinsky

William Blake and his Contemporaries

http://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/exhibitions/blake/blake.htm

William Blake Archive

http://www.blakearchive.org/blake/

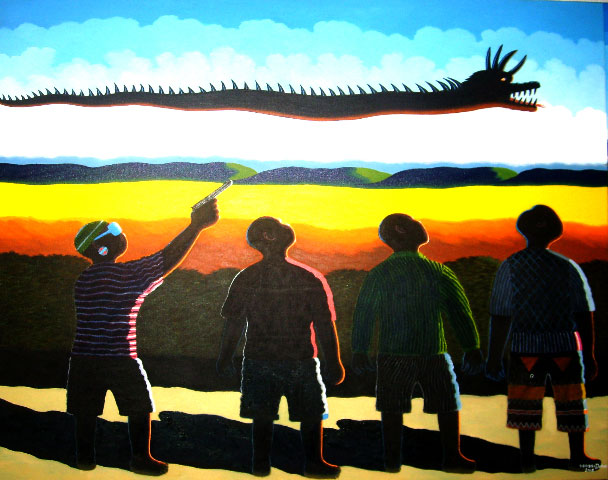

![bothas_emergency[1]](https://nladesignvisual.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/bothas_emergency1.jpg?w=614)