Biography

Penny Siopis is a South African of Greek descent. She was born in 1953 in Vryburg in the northern Cape. She mainly focuses on issues of race and gender, both in history and contemporary society. She also uses many different media and techniques to explore these themes, such as painting, photography, lithographs, film/video and installation of found objects.

Her earlier work, in the 1980’s, is characterized by her still lives, Baroque banquet paintings and ironical history paintings, focusing on questions of race and gender, as represented in public history, and memory. Her later works shows a concern with shame, violence and sexuality.

Infleunces

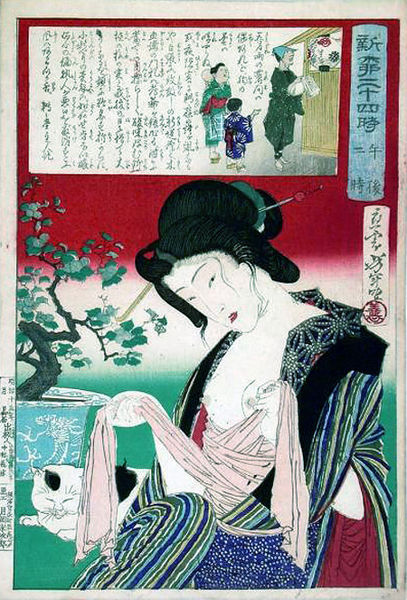

The themes of Penny’s work were influenced by the social environment in South Africa and especially by how women were treated and viewed throughout history and in contemporary South Africa. In her earlier work her style of painting was characteristic of classic Baroque style but used purposely as a comment on how the visual interpretation of gender and race in itself was a selective perception, and also a form of discrimination. By using the tradition of Western painting with its illusion of reality, she focuses our attention on prejudices often visually mis-represented in Western traditional art. Her later work shows influences of Japanese prints and is painted in an Expressionistic style.

Aims and Characteristics

Through her work Penny covers diverse areas of focus, and themes, reflecting the social and political changes in South Africa. She also uses many different media and techniques to explore these varied themes. She also used random objects in her work, to comment on colonialism, gender, and discriminatory practices of all kinds. To Penny Siopis each found object has its own past, and once played a role in someone’s life. Possessions embodies people’s personal memories and experiences, but have also become a part of the wider social history and symbolism.

Brief Outline of Penny Siopis Work:

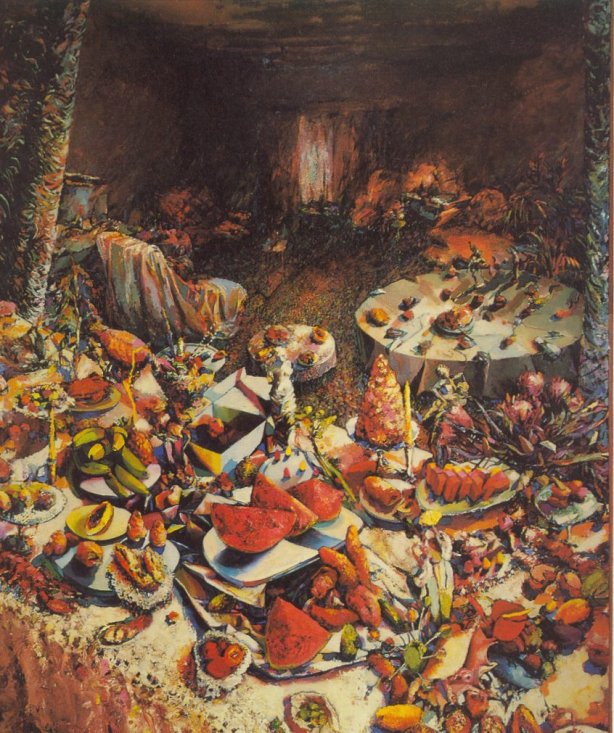

1980”s; Her early work in the 80’s were of mainly of cakes. Her family owned a bakery. Penny Siopis became well known for her Baroque banquet paintings such as “Melancholia” during this period. The subjects of Siopis’s artworks during the mid 80’s were mainly banquets, painted in oil with incredible attention to detail.

In these paintings with their rich colour, she copies the texture of lace cloths and doilies, using a domestic icing syringe and literally wove the patterns out of paint. In these Baroque Banquets, the paint becomes the embodiment of emotion. The Paint also becomes a metaphor for the human body, as the thick oil paint dries rapidly on the surface and dries very slowly on the inside, just like emotional hurt seemingly heals on the surface but inside it takes a long time to heal. This also evokes associations with other organic matter, flesh, in particular, that changes in time, congealing, forming skins, and losing its juices.

The impasto brushwork makes real shadows that add to the dramatic painted shadows.

Her work during this time period already showed her interest in gender issues as well as her interest in objects used as a metaphor, comparing the way in which women’s bodies are offered, to the presentation of food at banquets.

After she returned from her 6 month stay in France, she painted a series of “Ironic History,” commenting on the mis-representation of history, by Western patriarchal society. Examples of this period is “Piling Wreckage upon Wreckage,””Dora and the Other Woman” and “Patience on a Monument.” She used random objects in her work, which commented on colonialism, gender, and discriminatory practices of all kinds.

1990’s: In the next stage of her development she extended her range of media from oil paints and collage techniques, and incorporated her love of details, of debris, and of layers of association, to include monumental installations of found objects, film and video.

“Long I have been intrigued with the idea of an object as narrator. As the saying goes, “If walls (chairs, lamps, cutlery, or bowls) could talk, what tales they would tell?”

To Siopis each found object has its own past, and once played a role in a life, and embody personal memories and experiences, but have become a part of social history. Cumulatively, massed together in wall embrasures, built into mounds or strewn across a floor, the different objects which make up Siopis’ installations become integral parts of a new whole. History and personal memory are dissected, autopsied and diagnosed. Her film “Verwoerd Speaks” which was produced for the exhibition “Truth Veils” at Wits University, coinciding with the TRC: “Commissioning the Past“. The film shows her interest in the ‘found’ object as symbolic of the transition between public and private.

Definition of Installation art: It can be either temporary or permanent. Installation artworks have been constructed in exhibition spaces such as museums and galleries, as well as public and private spaces. The genre incorporates a broad range of everyday and natural materials, which are often chosen for their “evocative” qualities, thus making a statement about something. Installations also includes new media such as video, sound, performance, immersive virtual reality and the internet. Many installations are site-specific in that they are designed to exist only in the space for which they were created. – Encyclopedia

“The expression of history in things is no other than that of past torment”.

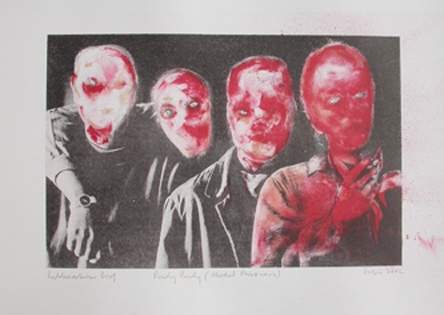

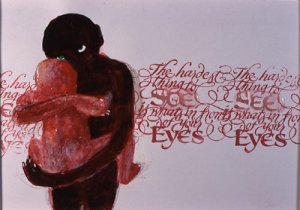

2000 – 2007: The next stage of her development is represented by her “Pinky Pinky” and “Shame” series which incorporate most of the techniques typical to her artworks; oil paint and found objects – as well as glass paint and lithographs. In her Pinky Pinky series, she explores issues surrounding gender and the vulnerability of young teenagers in South Africa. ‘Pinky Pinky’ is described by Siopis as an urban legend which is constantly invented and reinvented through the telling of the story. It can be described as a hybrid creature: half human, half animal and being neither female nor male but both simultaneously.

The “Shame”series is visually beautiful because of the free forms and colours, but ugly in its message. The duality serves to represent the beauty and intimacy a girl’s body can encapsulate, but also the violence that can destroy it.

In these series of paintings she use thickly applied oil paint to create almost three dimensional forms, and almost tactile texture to explore her interest in prejudice, shame and “moral panic”. In these works she explores the psychology of ‘shame’ and ‘a poetics of vulnerability’,The predominating colours are pink and red. The effect created by these techniques makes the paintings feel alive with a close reference to flesh and skin. She explains her choice of medium by saying:

“Paint acts as flesh: It dries slowly, and is moist underneath for years. Eventually it cracks and wrinkles”.

One of the films included in the installation, To Walk Naked, is a short documentary about a particular instance in apartheid South Africa in which a group of black woman stripped in front of white policemen intent on bulldozing their homes, using their nakedness and ‘shame’ as a weapon of resistance.

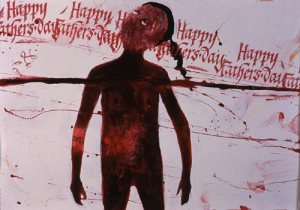

2007 – 2009: Her work during this period becomes more Expressionistic and is focused on giving expression to intense emotional states. In a series in which she describes as a ‘human tableau’ she focus on issues of emotional, sexual and physical abuse. She uses the associative and symbolic qualities of both her imagery and her chosen materials, including oils, liquid ink washes and viscous glue, to express her subjects. The process itself becomes important to her explorations.

“I start simply by being struck by an image. Something odd, curious, dramatic. The image can come from newspapers, books, movies, magazines, other art, my imagination or direct experiences. Many of these images are at once violent, erotic, tragic and beautiful. They are atavistic and elemental as well as social and analytical at the same time. Many allegorise deep human experiences like collapse, disorder, decay and formlessness. Process, chance and materiality (literally paint, ink, canvas, paper, glue acting on a surface) excite me, especially when unpredictable. I value this unpredictability. It creates a vital tension or energy between form and formlessness, balancing them on a knife-edge.”

2010: Her work has great changes from the 1980’s and although the female subject is still at the centre of her work, her aesthetic and techniques has shifted dramatically. In her exhibition, Furies, it is evident that the process is becoming increasing more important as part of exploring the subjects of her focus. “Line in particular takes on a real energy in these works, where it defines and dissolves form, burns into substance and bleeds across surface, goes its own way …”

“I am still excited and driven by the challenge materiality poses for depiction. Much of the sense and sensation in the paintings is embedded in the material itself: what floats, floods, flares, falls and fixes somewhere on the edge of form or formlessness. I am fascinated by the strangeness and openness of this process, which is intensified in the way I use my medium, viscous glue and liquid ink – a sort of choreography of chance and control, which offers extraordinary scope for new ways of associating and imagining.”

Some images emerge out of the medium itself. Others are sourced, from Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints and 12th-century scroll paintings (such as ‘hungry ghosts’ and ‘hell’ scrolls), showing scenes of sexuality and states of disaster.

“As remote as these references might appear, they resonate powerfully for me with things we might see or imagine in our contemporary moment. “

2011 In her “Who’s Afraid of the Crowd?”, exhibition she continues her interest in the tension between form and formlessness, figure and ground. In this exhibition she moves away from her predominant use of red and pink, that she started to use in her “Pinky Pink” series. Her new body of work draws on the idea of ‘the multitude’. One source is Elias Canetti’s “Crowds and Power” (1960), where Canetti’s swarms, masses, fires, rivers, seas, forests stimulate her to reimagine the relation between the individual and the multitude, and between the individual part and the mass. As before, her medium and process of working are as much conceptual as they are the means to create an image; both in her ink and glue paintings and her 8mm home movie footage she uses to compose her video. While she uses references from historical catastrophes in these paintings, like the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, she is more interested in in visual analogies suggested by process and medium, than the actual pictorial depiction.

Analyses of Works

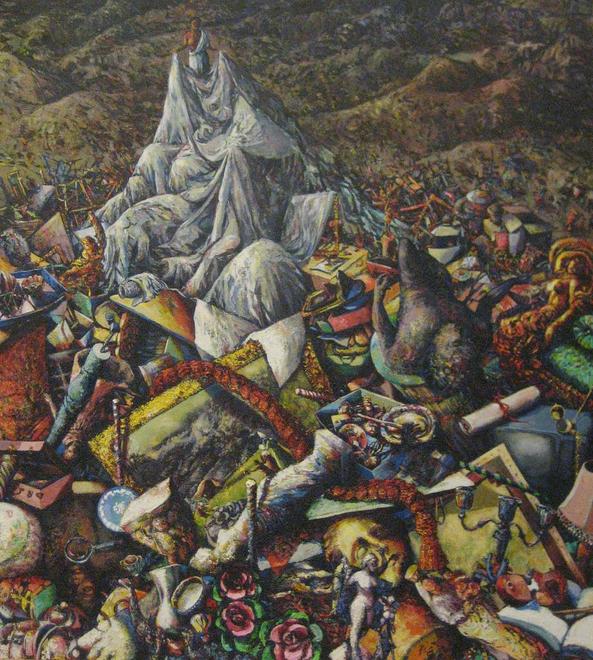

Patience on a Monument; ‘A History Painting,’ 1988, Oil Paint and Collage (Background to Dora)

A black female figure, semi–naked, sits on a pile of natural waste and the debris left behind by civilization – including fruit peelings, a stretched canvas, a dead bird, objets d’art, a skull, models of a pregnant womb and a broken heart, a little handbag, ornamental fittings, an open book, and two views of a bust of a black man. These objects have been compacted into appears to be a vast waste-disposal site. She is enthroned like some heroic statue, and peeling lemons in her lap.

A collage of photocopied images make up the landscape and the heaped debris. The photocopied images reflect entrenched perceptions: stereotypes of naked savages, the Boers, the British redcoats, scenes of pomp and heroism; The Landing of Van Riebeek, studies of political figures, national symbols and tourist souvenirs.

Traditional History Painting (recorded from a dominant white point of view) is satirised. The subtitle ‘ A History Painting’ – placed in inverted commas emphasises this irony.

The overlapping images symbolise the layering of history. Siopis questions history by reversing traditional roles. Patience, a black woman, towers above a history dominated by white supremacy but she sits peeling an lemon – an everyday activity – which undermines the glory of her position. Lemon, bitter fruit, may refer to the bitter plight of black women in history. It is also found in Dora and the Other Woman. Patience is anonymous, but she is 3-dimensional and real compared to the flat chaos of history around her. Patience is “anti heroic, an inversion of Liberty leading the people”by Delacroix . Liberty was a white imaginary heroic woman leading the people of Paris and Patience is black and indifferent to the chaos around her.

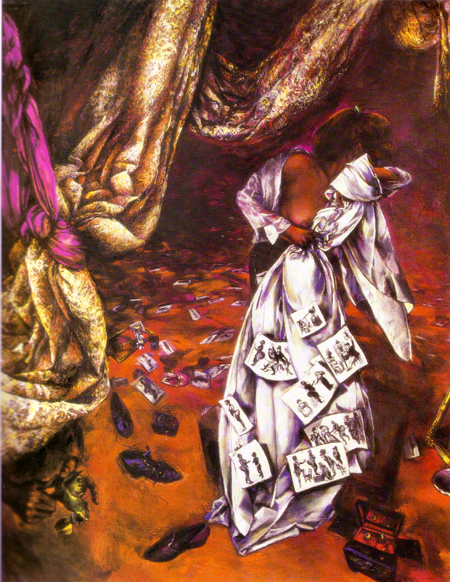

Dora and the Other Woman 1988 (Pastel on Paper)

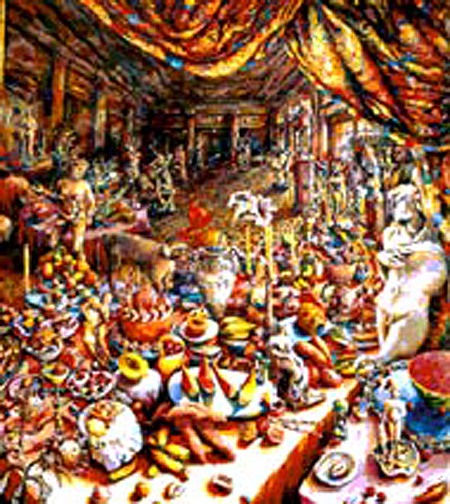

“Dora and the other Woman” is an example of one of Penny Siopis’ women in history paintings after she returned from a 7 month trip to Paris in 1986. It can also be seen as a continuation of her earlier style of painting and themes of her detailed Baroque Banquets in which the depictions of extravagant food and accompanying brocades and lacy finery were used as a metaphor, comparing the way in which women’s bodies are offered, to the presentation of food at banquets. Through most of her artworks, she used random objects, to comment on colonialism, gender issues, and discriminatory practises of all kinds.

In this painting she combines the stories of Saartjie Baardman and Dora, a young Viennese bourgeoisie woman from the turn of the 20th century, to make a statement about gender issues. Dora was sent by her father to Sigmond Freud for treatment for “hysterical unsociability” when a suicide note from her was discovered. Her “hysterical unsociability” or her seeming psychological problems were related to her social background, because in that patriarchal environment she could make no independent choices and she was also used as a pawn in a game between her father and the husband of her father’s mistress; “give me your wife and you can have my daughter.”

The ‘Other Woman’ in the title is on one level a reference to the ways in which hysteria was seen as a symptom of the ‘otherness’ of women in so-called ‘scientific’ studies of the disorder. To Penny Siopis Dora’s hysteria was seen as a sign of women’s resistance to patriarchal domination and as a protest against the “colonisation of her body.” For her Freud’s comment about female sexuality being “the dark continent” of psychology connects Dora and Saartjie. Africa was known as the dark continent.

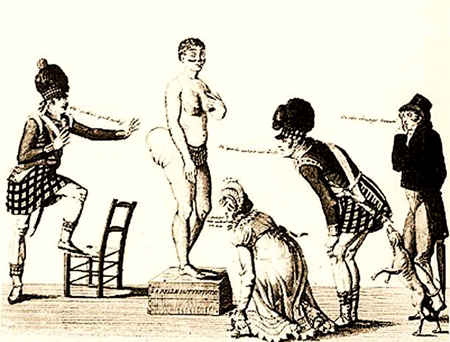

Saartjie Baartman “the other woman” was a Khoisan woman shipped from South Africa to Europe in 1810, and toured as a sideshow spectacle in England and France. Penny also sees a similarity in the way the nineteenth-century Europeans interpreted Saartjies’s body shape as a sign of her primitive sexuality, and how they viewed Dora’s hysteria as a marker of dark primal urges awaiting discovery by explorers or scientist of the time. The degrading treatment both Dora and Saartjie received was because of their sex and in Saartjie’s case, her race as well.

The painting has a baroque background, with lavishly draped curtains. Just like baroque paintings that typically had a strong sense of movement, Penny uses swirling spirals and upward diagonals, in the brocade-like drapery with a strong rich colour scheme of golds, purples and orange. Like most of her paintings it has great attention to detail and is theatrical in feel. The whole feel of stage-like setting may also suggest enacted truths rather than the real truth, such as is found in societies with prejudices. The light in the painting is artificial with no daylight, again perhaps suggestion an artificial environment.

Everything in her paintings were chosen to create a certain effect. She for example deliberately uses the rich realistic colour, style and composition found in “classical high art” of baroque as a play on conventions. Even the illusion of reality on a 2 dimensional surface, reflects how she sees the politics of representation; where the visual interpretation of gender and race in itself was a selective perception, and also a form of discrimination.

“I work within the tradition of Western painting in ways which attempt to turn its own values

against itself, to show that it is not only representation of politics that is an issue, but the politics of representation as well.” Penny Siopis

She further emphasizes this aspect through the nineteenth century illustrations of Saartjie pinned to the drapery on Dora’s body, and scattered on the floor. These illustrations show Saartjie being looked at from all angles, often with an aid of a magnifying glass or telescope. It was mostly through optical means that Europeans had access to the ‘exotic’ other. To Penny Siopis these pictures also shows how prejudice operates in visual representation of a subject. To the 19th century Europeans these images of Saartjie were objective, harmless or “natural.” For her Dora and Saartjie epitomise those kind of (mis)representation of cultural identity, gender and race. This aspect of selective perception, in my opinion, is further emphasized by the box cameras, and empty frames that are scattered on the floor.

Objects such as shoes, purse and a jewelry box are also scattered on the ground, referring to women as an adornment or discarded possessions, a theme she also explored in her earlier banquet paintings. The open jewelry box can also refer to sexual disclosure. To Penny looking may also be seen as a way of possessing or colonising.

Just visible from behind the curtains on the lower left hand corner of the painting are two black hands peeling a lemon. This could perhaps allude to a bitter history as it is also found in another of her ironical history paintings of the time “Patience on a monument,”or may refer to the bitter plight of black women in history, or it could allude to unpeeling the layers of misrepresentation of women in history. The way that the hands are also half concealed by the curtains could also suggest the hidden sexual discriminations against women in history.

The focal point of the composition is Dora standing on a box as on display. Her face and most of her body is covered by a white drape and one feels as if she is hiding from the viewer in her humiliation, but one also wonders whether Penny is also using this to show the dehumanizing aspect of sexual stereotypes, where the individual personality is not important.

Slings and Arrows (2007). oil and glue on canvas

In “Slings and Arrows” Penny Siopis directly refers to Frida Kahlo’s “ Wounded Deer.” Both artists dealt with feminist issues and in these paintings in particular with pain and a feeling of helplessness in the face of fate.

The title “Slings and Arrows” is derived from Hamlet’s famous soliloquy by Shakespeare.

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

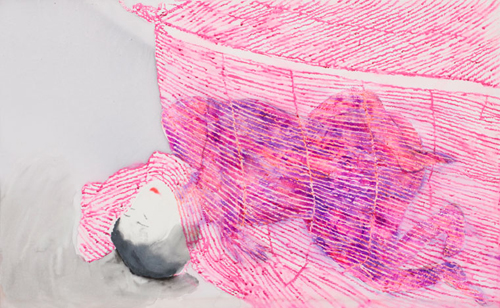

It is part of Penny Siopis’ 2007 exhibition “Lasso”, which was described as “intimate narratives that express the poetics of vulnerability”. The Expressionistic series of paintings explores the pain experienced by victims of extreme trauma and focuses on the stories of disempowered women and children. The subjects deal with childhood sexual and physical abuse as well as feelings of displacement and prejudice that many women are forced to experience at the hands of others.

Depicted in “Slings and Arrows”, is an image of an animal-human hybrid wounded by arrows – a body of a deer with a human head. A deer is normally seen as a gentle innocent creature but also a creature that can be mercilessly hunted without any regard to its its feelings. In this Penny may be referring to the aspect of objectification of women’s bodies, which leads to the physical abuse of women and children. The hybrid creature also refers to to the themes she started to explore in her “Pinky Pinky” series where violent physical encounter left the victims as something “half-animal, half human, half woman, half nothing.”

”Exposed to the trauma of extreme abuse, a person’s soul is left torn and depersonalised.”

Penny uses an Expressionistic style, with loose expressive brushwork, to express a feeling of pain and hopelessness in the face of fate. This is further emphasized by broken rope around the deer’s neck, as if it tried to escape its fate and the pain inflicted by the arrows of fate. One almost feels as if the deer was already wounded while helplessly held in captivity.

There is no background or depth in the painting and the creature faces the viewer against a backdrop of pinks,red and grey colour brushstrokes, that gives the feeling that the hybrid animal is engulfed in a sea of emotion. In my opinion, the lack of space in the painting helps to focus the feeling of the creature being trapped and emphasises the intensity of emotion. It is visually like moments of intense fear or pain, where everything else disappear and everything becomes focused in that emotion.

Penny also uses the characteristic pink and scarlet tones, started in the “Pinky Pinky” series, evocative of blood emanating from open wounds to bring emphasis to the overall feeling of pain. The technique she used to depict the image in itself also becomes expressive; a visible expression of the emotions. The film of polished glue once dry resembles the surface of human skin that is vulnerable and prone to tearing. By allowing the paint and glue to curdle and drip beyond the edge of her surfaces, she captures the excesses of emotion that characterises the subject of her painting. While enamel applied to ink or paint serves to sharpen the image, it also allows the emotions and tensions that exist within image to be heightened.

The painting is visually beautiful because of the free forms and colours, but it is ugly in its message. The duality seems to represent the beauty and intimacy a girl’s body can encapsulate, but also the violence that can destroy it. This seems to reinforced by the predominant pink colour which is generally the colour associated with little girls but here Penny uses it to show wounds, and broken skin.

Penny is well known for her layers of associations of symbolism and in making such direct reference to Frida’s “Wounded Deer” she may also be referring to the fact that although Frida portrays her own experiences, and her personal pain, Frida’s personal pain also “have wider social and cultural symbolism. “ In other words, Frida’s personal suffering becomes symbolic of the suffering and helplessness of women worldwide. Which Penny describes as “ objects that are emblematic of a merging of private and public worlds.”

Bibliography

African Success

http://www.africansuccess.org/visuFiche.php?id=576&lang=en

Answers.Com

http://www.answers.com/topic/installation-art#ixzz1vOBm7aD9

The Artists Press

http://www.artists-press.net/penny-siopis/penny-siosis.htm

ArtSpace

http://artworksartspace.blogspot.com/2011/04/grace-kotze.html

Artthrob

http://www.artthrob.co.za/02sept/listings_gauteng.html#goodman2.

http://www.artthrob.co.za/99sept/artbio.html

Camwood

http://www.camwood.org/salah.htm

Gender in Art – Twentieth Century – Artist, Social, Female, and Roles – JRank Articles http://science.jrank.org/pages/9461/Gender-in-Art-Twentieth-Century.html#ixzz1vCoF9RwO

Marry Carigal – Blogspot

http://corrigall.blogspot.com/2010/09/siopis-at-brodie-stevenson.html

Resistance Art in South Africa, Sue Williamson, Double Storey Books, Cape Town, 2004

Stevenson Art

http://www.stevenson.info/artists/siopis.html

http://www.stevenson.info/exhibitions/siopis/index2011.htm

Writework